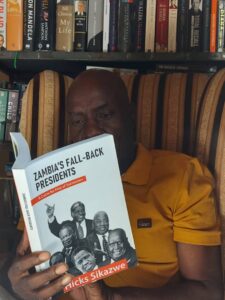

Hicks Sikazwe reading Zambia’s Fall-Back Presidents, a Curse for fear of succession

…read Hicks Sikazwe’s’ Zambia’s Fall-Back Presidents, a Curse for fear of succession!

Book Review

Title: Zambia’s Fall-Back Presidents, a Curse for fear of succession

Author; Hicks Sikazwe

Our Leaders, Succession, and the truths we hold ………….

Kenneth Kaunda, the first nationalist president had to be forced out of power in 1991 when he still had three more years to serve before another general election. In 1978 Kaunda blocked his former vice-president Simon Mwansa Kapwepwe, long-time opposition rival Harry Mwaanga Nkumbula and businessman Robert Chiluwe from contesting elections to challenge him. He had in 1972 imposed a one-party dictatorship.

For 27 years in power, he had not prepared any one to take over from him. Naïvely in December 1990, he repealed Article 4 of the Constitution, opening the floodgates to multiparty politics and allowing parties, other than UNIP, into the political arena. Believing that he and UNIP would win again, Kaunda bowed down to pressure mounted by unionist Frederick Chiluba’s new political grouping, the Movement for Multiparty Democracy (MMD), and agreed to hold elections in November 1991—he lost disastrously.

Chiluba, who used the labour movement, the Zambia Congress of Trade Unions (ZCTU), as a spring board to venture into politics and dislodge Kaunda in a popular uprising of an election was, as head of state and government the queerest among successors. First he introduced a draconian law to bar Kaunda from challenging him in 1996 on the basis that KK’s parents came from Nyasaland, now Malawi. Then at the end of his second and final term he wanted to manipulate everything from people to the Constitution so that he could storm into a third term, but a broad based countrywide popular uprising intimidated him into withdrawing; he claimed in a television broadcast that in fact he had never intended to seek a third term in office.

By the time Levy Mwanawasa, who took over from Chiluba in a night anointment, died, there was again no indication that a successor had been prepared. The emergence of a UNIP cadre, Rupiah Banda, (appointed Levy’s vice-president, the book says, had strings attached.

Unpredictable and erratic Michael Sata, another UNIP Stalwart, won the 2011 polls as a rebel from mainstream leadership in the MMD and UNIP. So the election of Edgar Lungu president in 2016 provides even more interesting debate in this leadership narrative. Shockingly after Sata died, a white man, Dr Guy Scott, had to spring up as a stand-in president for 90 days, in a black independent nation because of a flawed system entrenched by colonial legal provisions still existent amongst what was supposed to have been liberated indigenous statutes.

Thus, the fear of succession or the failure to groom successors by leaders at the political helm in Zambia, the author argues, has been a recipe for dictatorship and has rendered the country’s return to democracy in 1990 cosmetic, a wasted effort and at the most a fruitless exercise.

But also critical in this highly analytical narrative is on the origins of most Zambia’s Presidents. Kaunda who has been the only one to publicly confirm that though born in Zambia his parents came from Malawi, there have been follow up accusations claiming that even Mwanawasa, Banda Lungu could have Malawian roots, While Chiluba was mired in a parentage mess with insinuations that after all he was a Congolese. But was Chiluba really a Congolese? However, all claims have been rebutted. Sata himself who accused others to be foreigners was pointed to have come from Tanzania. Why do these claims keep emerging? Find the answer in the book.

Over succession, the author heaps blame on KK and UNIP that they did not prepare successors. He also takes on the opposition insisting that opposition parties have since 1991 been uninspiring lot. But more importantly the country is being ruled by either UNIP surrogates or by people fostering traits of the former ruling party.

The book also reveals that Hakainde Hichilema should have long been President before RB, Sata or Lungu but How? Find out from the book. But has he got chance and capacity to win this year’s elections? Check the narrative in Zambia’s Fall Back Presidents.

Author Sikazwe, says the truths we hold about our leaders should be discussed to build and entrench democracy the country reverted to in 1991. He also adds that Zambia can only navigate the future when the country learns from the past.

In the foreword University of Zambia Lecturer in the Department of Media and Communications studies Dr Sam Phiri writes:

This is a story about Zambia. It is a story that is told from a perspective never perceived before and since. It is the kind of history that looks at the ‘everyday events’ from a different, critical and a much more penetrating view point. We are made to see the trees from the forest!

Essentially, it’s a tale about Zambian presidents and how they became presidents. According to Hicks, in normal circumstances, all the six or seven presidents, should not have risen to that top office, except for chance: that is, being in the right place at the right time, or because Zambians did not think through the issue much more intimately.

This is the central thought in this highly controversial book. Hicks declares that all Zambia’s presidents, since 1964, have been accidental. Mostly, they are second choice leaders. More disturbing though, is the claim that all along, Zambia has been led by people “some without any clear professional background, political know-how or definitive country of origin.” In short, our leaders have been unprofessional, and non-indigenes.

Now, that is something to chew upon. However, three things are pertinent here: The author argues that some Zambia’s presidents, have had no “clear” professional background to qualify them to lead this nation. Secondly, they have all been political novices, or green horns, who have fumbled along as they led the nation. Lastly – perhaps more intriguing – Hicks argues that they all have no “definitive country of origin.”

These three points are highly contentious, but Hicks says what he wants to say. Right through the text, he appears to have done his background checks well. That is a major strength of this book. It is written by an experienced and highly intelligent journalist who dares to go into areas where none has been before.

Thus Hicks further argues that Zambia has been ‘miss-led’ not only because of the above three rather scary factors, but also because of the absence of some definitive and predictable succession programmes. Herein lies another of the profligate claims in this book. Hicks squarely blames Zambia’s lack of political and economic success, in its 56+ years of independence, on the people’s repeated failure to exercise caution, and their failure to scrutinise individuals sent into State House.

Comparatively, whereas properly led countries like Singapore have risen from the marshlands into first world status within 50 years because of a committed, professional and indigenous leadership, Zambia with all its great natural and other resources, remains mired in poverty, hunger and disease because it is “cursed” by foreign, disinterested and poor political leadership.

How that leadership flaw should be addressed, is however, not sufficiently addressed (except that Zambia needs a new generation of politicians) in this highly controversial, but penetrating analysis. Still, by pointing these issues out, the author lets the reader dissect and determine the solutions to Zambia’s political, social, cultural and economic problems.

What is true however is that Hicks writes as he pleases. That is the hallmark of a person who is politically unspoilt, one who has spent years advocating for open and free public debate on various issues including this one. He pulls no punches and gives it all, as he sees fit.

I am aware that one publisher kept the book at pole’s length because of the controversial stances taken in this historical narrative. Suggestions were made to have sections of the book cut out. This did not seat well with Hicks. He was furious. How could he countenance being censored in that manner?

Like several other people, he believes in telling the history of the nation from his perspective and that nothing should be sacred in a free and democratic society. Only truth matters. And indeed it should be so. His views, like any other, should be placed unto the public domain and be given a chance to be tested by those with different historical viewpoints. That is what progress is all about.

For now, I can only encourage everyone to ‘read on, and enjoy the intellectual ride.’ After all, as Prof Munyonzwe Hamalengwa of Zambia Open University would say: “Thoughts are free…” and I add that reflections such as these, should never be imprisoned.

Available on Amazon.com, 320 pages, Published by Bookleaf Publishing, India. This is a book we must all lay our hands on. Copies can be accessed from the author on 0955/0966 92961. /By A Correspondent.